The turn of a new year always brings a tinge of hope with it. Historically I have found a kind of new motivation whenever this hope manifests itself. This was by no means my quietest New Year’s Eve: I had a short celebration with some extended family, put the baby to bed, had some tea while I read a book, and kissed my wife when the ball dropped. It was perfect.

But I didn’t feel the need to try and reinvent any certain aspect of my life. To be completely honest, this is comforting to me. I’ve never had a new year where I didn’t have a resolution and I’m taking this as a sign of personal growth. Being content with who you are and where you are in life is something many of us put an enormous amount of time, effort and money into realizing. I am not immune. Now I’ve come to this point and I am happy to be here; although a part of me knows this feeling is fleeting.

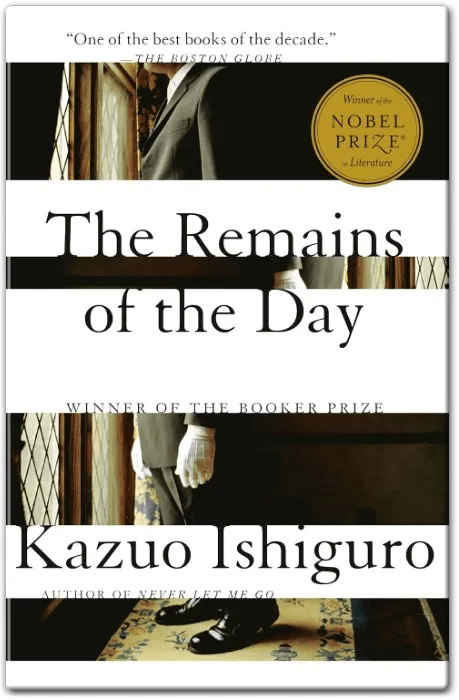

In 2025 I read seventeen books. While I’m not setting a “number-of-books-read” goal this year, I am setting a goal of intentionality. The trend perpetuated by apps like Goodreads or Fable of “reading goals” has, at times, driven me to simply get pages behind me as opposed to getting ideas burned into my memory. To that end, I’ve begun annotating books more; a practice I started late last year during my read-through of Karamazov. I’m finding that marking passages, ideas, and lines that stand out to me as I’m reading with tabs and writing in the marginalia of pages my initial thoughts force me to come back to them when I’m sitting with a book once completed.

However, the real magic happens when I sit with a book after I’ve completed it. I’m trying to purposely not read other reviews or user thoughts online so that I can try and pull my own themes out of each book, wrestle with them on paper, and come out the other side with a coherent grasp of each piece. This has been the most impactful change to my reading I’ve made since November, and is something I intend to continue. Some of that might end up here, some won’t; you’re welcome to follow along.

Currently reading: My Struggle (Book 1) – Karl Ove Knausgaard

Currently listening:

Happy New Year!